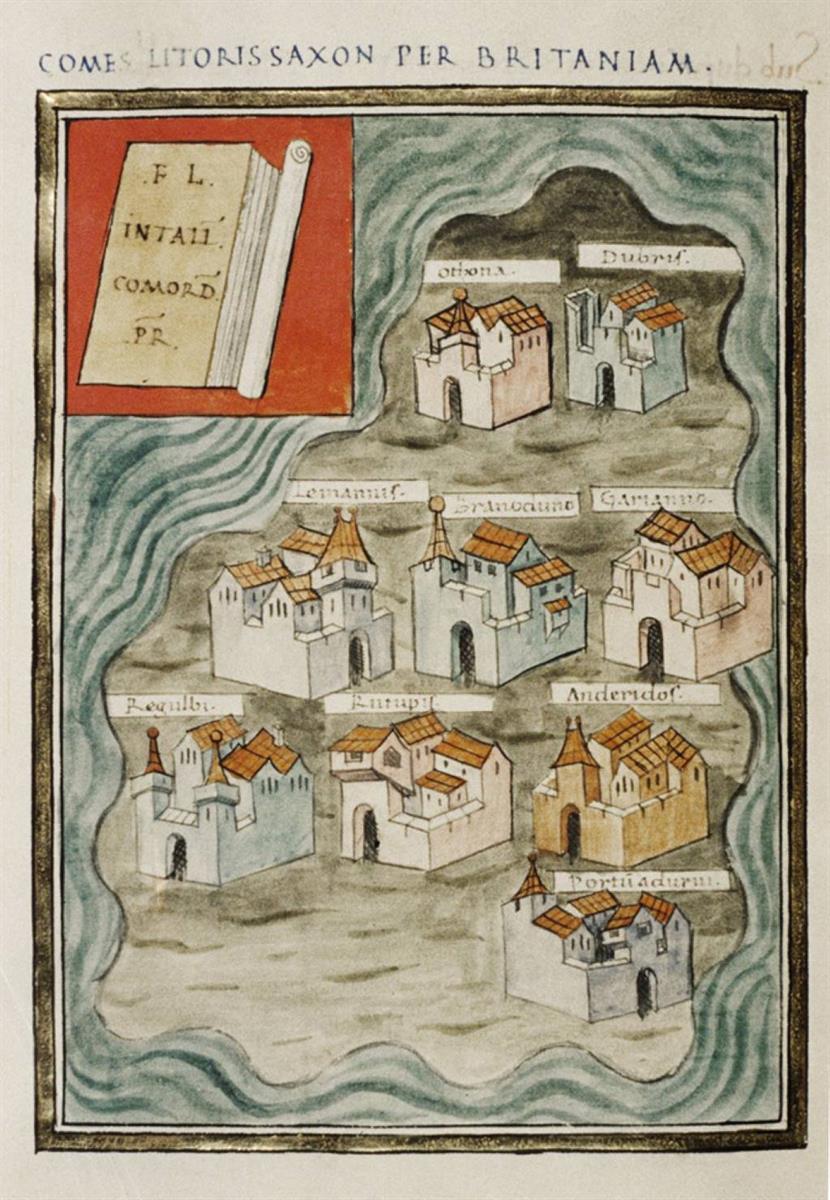

The page of the manuscript of the Notitia Dignitatum in the Bodleian Library, Oxford showing the command of the Count of the Saxon Shore. The fort at Lympne (known as Portus Lemanis) near Lyminge is shown on the left of the middle row. (©Wikimedia Commons)

The page of the manuscript of the Notitia Dignitatum in the Bodleian Library, Oxford showing the command of the Count of the Saxon Shore. The fort at Lympne (known as Portus Lemanis) near Lyminge is shown on the left of the middle row. (©Wikimedia Commons)

We have been delighted by the positive response to the launch of the Royal Saxon Way. Many people have already enjoyed walking the route, experiencing the varied sea, river and landscape to be enjoyed along the way. Many too have responded well to the idea that a number of churches on the route were connected to powerful women who founded them or served as abbesses in the 7th and 8th Centuries, and that these women should be celebrated. But what is Saxon about the route? After all, it is commonly said that in the period after the end of Roman rule, Kent was settled by the Jutes rather than by Saxons?

The reality is that we do not know precisely where the migrants who came to the southern and eastern parts of Britain in the 4th, 5th and 6th Centuries actually came from or what they called themselves. Recent DNA research is demonstrating that a substantial proportion of the population of this area at this time, perhaps as much as 40%, had its origins in the north west of Continental Europe. So we can readily accept that there were migrants to Britain who came from the area we now think of as Germany, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Belgium, but as they had no written language the people of that time have left no written records of where exactly in this region they came from, nor what they called themselves. So all we do know about them was written by others. These were almost entirely churchmen because on the whole, these were the only people who could read and write. Some were contemporaries living in Continental Europe. We also have one book written in the 6th Century in the west of Britain, outside the area settled by these migrants, where literacy and church institutions had survived the fall of the Roman Empire. The final source is the descendants of these migrants, who became Christian, and some of whom, as churchmen, learned to read and write. They too have left records about this early period, but written from the viewpoint of a later date. As churchmen, all these authors viewed themselves as the heirs of Roman Latin culture, and this influenced how they thought and what they wrote.