Edward Hasted visited Lyminge towards the end of the 18th Century when he was compiling his mammoth multi-volume History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, first published in successive volumes from 1778, with a second edition from 1797. He had a rather poor view of the parish, noting that:

‘the greatest part of it [is] on high ground, where it is a dreary and barren country of rough grounds, covered with woods, scrubby coppice, broom and the like, the soil being an unfertile red earth, with quantities of hard and sharp flint stones among it. In that part adjoining to the Stone-street way, is Westwood…and not far from it, two long commons…the one called Rhode, the other Stelling Minnis…there are numbers of houses and cottages built promiscuously on and about them, the inhabitants of which are as wild and in as rough a state as the country they dwell in.’

In a form of back-handed compliment, Hasted did concede that the land around the spring in Lyminge was ‘far from unpleasant’, and he noted that the land of the valley bottom around the course of the Nail Bourne was fertile with good meadows. This was where the majority of the population was focused.

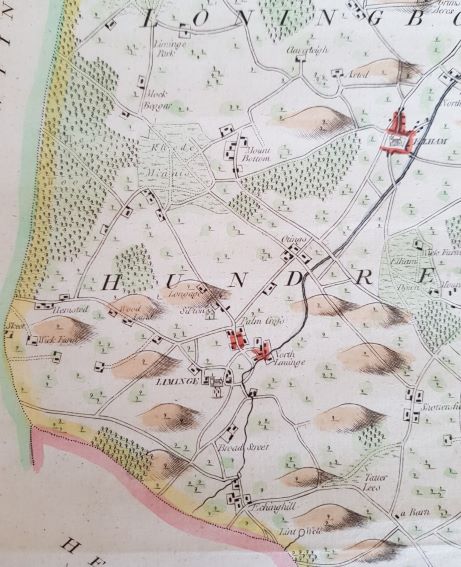

Detail from Hasted's map of the administrative districts of Loningborough and Folkestone Hundreds, showing the area of Lyminge c1778 (©Rob Baldwin)

Detail from Hasted's map of the administrative districts of Loningborough and Folkestone Hundreds, showing the area of Lyminge c1778 (©Rob Baldwin)