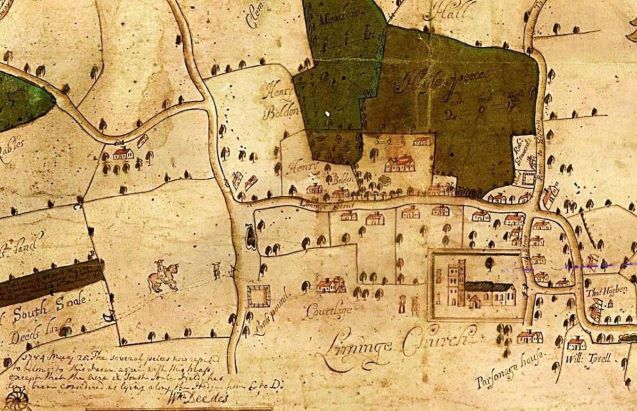

Archbishop Courtenay (1381-96) received permission from the king to demolish some of his neighbouring manor houses to repair his castle at Saltwood. This may have removed much of the complex, but probably not all of it. Court Lodge was still standing in 1685, when it was illustrated on a map drawn by William Hill. The church is quite accurately depicted on this map, so it is possible this drawing of Court Lodge is accurate too. If so, this is probably just a part of what was once a very grand complex of buildings stretching across the whole area that is now occupied by Court Lodge Green and the New Churchyard, the area lying west of the Old Churchyard boundary wall. The New Churchyard, where the War Memorial now stands, was once known as Abbots Green. Burial began in the northern part only after it was allocated for this purpose in 1855, and in the southern part not until after the First World War. Prior to this, it was a meadow. Canon Jenkins says that it was covered with building remains that were destroyed by his predecessor in order to build the Rectory Farm, that used to stand on Rectory Lane. But as the area is now densely covered with graves, it is unlikely we will recover much more information about the buildings that once stood here.

Detail from Thomas Hill’s map of 1685 showing the area around the High Street, including Court Lodge and the church (©Lyminge Historical Society)