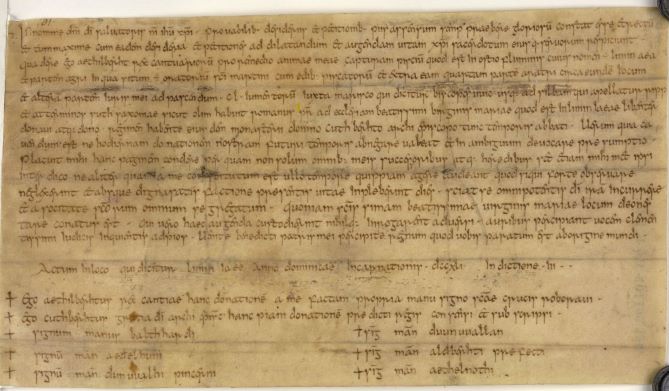

Charter of Æthelberht II dating to 741 recording the grant of a fishery on the River Limen (the East Rother that flowed into the sea near west Hythe) to the church of St Mary at Lyminge. This charter was possibly written in the monastery at Lyminge (© British Library)

Charter of Æthelberht II dating to 741 recording the grant of a fishery on the River Limen (the East Rother that flowed into the sea near west Hythe) to the church of St Mary at Lyminge. This charter was possibly written in the monastery at Lyminge (© British Library)

Many monasteries in Kent were founded by the Kentish royal family. They were usually run by women, dowager queens like Ethelburga or princesses like Ethelburga's niece Eanswythe at Folkestone, who never married. Monasteries were high status communities, and the nuns generally came from an aristocratic background. Royal abbesses kept abbeys firmly under the control of the royal family, allowing them to offer accommodation to the king and his retinue as they processed around the kingdom, dispensing justice and ensuring that the king both saw what was going on and was seen by his people. As royal and aristocratic estates, we know that monasteries consumed luxury goods too, and it seems that at Lyminge, much use was made of the port at Sandtun (modern West Hythe) where pottery, glassware and fine wine were imported from Europe.

But the other significant, as well as unique, role of monasteries was as powerhouses of prayer. It was believed by our Early Medieval ancestors that there was a constant battle between the forces of Good and Evil. The duty of nuns and monks in the monasteries was to pray, invoking the support of God and the saints to support the king, the royal family and the kingdom as a whole. The role of the royal abbesses leading the fight in this spiritual battle was considered just as important as the role of the king and his nobles defending the kingdom on the temporal battlefield.